Marc Mitscher on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Marc Andrew "Pete" Mitscher (January 26, 1887 – February 3, 1947) was a pioneer in naval aviation who became an admiral in the

Mitscher took an early interest in aviation, requesting a transfer to aeronautics while aboard ''Colorado'' in his last year as a midshipman, but his request was not granted. After graduating he continued to make requests for transfer to aviation while serving on the destroyers and . Mitscher was in charge of the engine room on USS ''Stewart'' when orders to transfer to the Naval Aeronautic Station in

Mitscher took an early interest in aviation, requesting a transfer to aeronautics while aboard ''Colorado'' in his last year as a midshipman, but his request was not granted. After graduating he continued to make requests for transfer to aviation while serving on the destroyers and . Mitscher was in charge of the engine room on USS ''Stewart'' when orders to transfer to the Naval Aeronautic Station in

On May 10, 1919, Mitscher was among a group of naval aviators attempting the first

On May 10, 1919, Mitscher was among a group of naval aviators attempting the first

Between June 1939 and July 1941, Mitscher served as assistant chief of the

Between June 1939 and July 1941, Mitscher served as assistant chief of the

During the

During the  The first of the carrier squadrons to locate the Japanese carriers, Waldron bore down upon the enemy. He brought his group in low, slowing for their torpedo drops. With no fighter escort and no other attackers on hand to split the defenders, his group was devastated by defending Japanese Zeros flying combat air patrol (CAP). All fifteen

The first of the carrier squadrons to locate the Japanese carriers, Waldron bore down upon the enemy. He brought his group in low, slowing for their torpedo drops. With no fighter escort and no other attackers on hand to split the defenders, his group was devastated by defending Japanese Zeros flying combat air patrol (CAP). All fifteen

Returning to the Central Pacific as Commander, Carrier Division 3, Mitscher was given primary responsibility for the development and operations of a newly formed

Returning to the Central Pacific as Commander, Carrier Division 3, Mitscher was given primary responsibility for the development and operations of a newly formed

The fleet had recently completed operations in the Gilbert Islands, taking

The fleet had recently completed operations in the Gilbert Islands, taking

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

, and served as commander of the Fast Carrier Task Force

The Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 38 when assigned to Third Fleet, TF 58 when assigned to Fifth Fleet), was the main striking force of the United States Navy in the Pacific War from January 1944 through the end of the war in August 1945. The task ...

in the Pacific during the latter half of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

Early life and career

Mitscher was born inHillsboro, Wisconsin

Hillsboro is a city in Vernon County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 1,397 at the 2020 Census. The city is located within the Town of Hillsboro. Hillsboro is known as the Czech Capital of Wisconsin.

Geography

Hillsboro is located ...

on January 26, 1887, the son of Oscar

Oscar, OSCAR, or The Oscar may refer to:

People

* Oscar (given name), an Irish- and English-language name also used in other languages; the article includes the names Oskar, Oskari, Oszkár, Óscar, and other forms.

* Oscar (Irish mythology) ...

and Myrta (Shear) Mitscher. Mitscher's grandfather, Andreas Mitscher (1821–1905), was a German immigrant from Traben-Trarbach

Traben-Trarbach on the Middle Moselle is a town in the Bernkastel-Wittlich district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It is the seat of the like-named ''Verbandsgemeinde'' and a state-recognized climatic spa (''Luftkurort''). The city lies in the ...

. His other grandfather, Thomas J. Shear, was a member of the Wisconsin State Assembly

The Wisconsin State Assembly is the lower house of the Wisconsin Legislature. Together with the smaller Wisconsin Senate, the two constitute the legislative branch of the U.S. state of Wisconsin.

Representatives are elected for two-year terms, ...

. During the western land boom of 1889, when Marc was two years old, his family resettled in Oklahoma City

Oklahoma City (), officially the City of Oklahoma City, and often shortened to OKC, is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The county seat of Oklahoma County, it ranks 20th among United States cities in population, a ...

, Oklahoma, where his father, a federal Indian agent

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with American Indian tribes on behalf of the government.

Background

The federal regulation of Indian affairs in the United States first included development of t ...

, later became that city's second mayor. His uncle, Byron D. Shear

Byron Delos Shear (May 12, 1869 – June 9, 1929) was an American politician who served as Mayor of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma in the 1910s.

Biography

Shear was born on May 12, 1869 in Hillsboro, Wisconsin, conflicting reports have been given o ...

, would also become mayor.

Mitscher attended elementary and secondary schools in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

He received an appointment to the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

at Annapolis, Maryland in 1904 through Bird Segle McGuire

Bird Segle McGuire (October 13, 1865 – November 9, 1930) was an American politician, a Delegate and the last U.S. Representative from Oklahoma Territory. After statehood, he was elected as an Oklahoma member of Congress, where he served four c ...

, then U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they c ...

from Oklahoma.

An indifferent student with a lackluster sense of military deportment, Mitscher's career at the naval academy did not portend the accomplishments he would achieve later in life. Nicknamed after Annapolis's first midshipman from Oklahoma, Peter Cassius Marcellus Cade, who had "bilged-out" in 1903, upperclassmen compelled young Mitscher to recite the entire name as a hazing. Soon he was referred to as "Oklahoma Pete", with the nickname shortened to just "Pete" by the winter of his youngster (sophomore) year.

Having amassed 159 demerits and showing poorly in his class work, Mitscher was saddled with a forced resignation at the end of his sophomore year. At the insistence of his father, Mitscher re-applied and was granted reappointment, though he had to re-enter the academy as a first year plebe

In ancient Rome, the plebeians (also called plebs) were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not patricians, as determined by the census, or in other words "commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

Etymology

The precise origins of ...

.

This time the stoic Mitscher worked straight through, and on June 3, 1910, he graduated 113th out of a class of 131. Following graduation he served two years at sea aboard , and was commissioned ensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diffe ...

on March 7, 1912. In August 1913, he served aboard on the West Coast West Coast or west coast may refer to:

Geography Australia

* Western Australia

*Regions of South Australia#Weather forecasting, West Coast of South Australia

* West Coast, Tasmania

**West Coast Range, mountain range in the region

Canada

* Britis ...

. During that time Mexico was experiencing a political disturbance, and ''California'' was sent to protect U.S. interests and citizens.

Naval aviation

Mitscher took an early interest in aviation, requesting a transfer to aeronautics while aboard ''Colorado'' in his last year as a midshipman, but his request was not granted. After graduating he continued to make requests for transfer to aviation while serving on the destroyers and . Mitscher was in charge of the engine room on USS ''Stewart'' when orders to transfer to the Naval Aeronautic Station in

Mitscher took an early interest in aviation, requesting a transfer to aeronautics while aboard ''Colorado'' in his last year as a midshipman, but his request was not granted. After graduating he continued to make requests for transfer to aviation while serving on the destroyers and . Mitscher was in charge of the engine room on USS ''Stewart'' when orders to transfer to the Naval Aeronautic Station in Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

, Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

came in.

Mitscher was assigned to the armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

, which was being used to experiment as a launching platform for aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engine ...

. The ship had been fitted with a catapult over her fantail

Fantails are small insectivorous songbirds of the genus ''Rhipidura'' in the family Rhipiduridae, native to Australasia, Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. Most of the species are about long, specialist aerial feeders, and named as " ...

. Mitscher trained as a pilot, earning his wings and the designation Naval Aviator. Mitscher was one of the first naval aviators, receiving No. 33 on June 2, 1916. Almost a year later, on April 6, 1917, he reported to the renamed armored cruiser for duty in connection with aircraft catapult experiments. During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the Navy established Naval Air Station Montauk in August, 1917, commanded by LT Marc Mitscher. Reconnaissance dirigibles

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early d ...

, an airplane, troops and Coast Guard

A coast guard or coastguard is a maritime security organization of a particular country. The term embraces wide range of responsibilities in different countries, from being a heavily armed military force with customs and security duties to ...

personnel were stationed at Montauk L.I. New York.

At this early date the Navy was interested in using aircraft for scouting purposes and as spotters for direction of their gunnery. Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

Mitscher was placed in command of NAS Dinner Key in Coconut Grove, Florida

Coconut Grove, also known colloquially as The Grove, is the oldest continuously inhabited neighborhood of Miami in Miami-Dade County, Florida. The neighborhood is roughly bound by North Prospect Drive to the south, LeJeune Road to the west, S ...

. Dinner Key was the second largest naval air facility in the U.S. and was used to train seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their technological characteri ...

pilots for the Naval Reserve Flying Corps The Naval Reserve Flying Corps (NRFC) was the first United States Navy reserve pilot procurement program. As part of demobilization following World War I the NRFC was completely inactive by 1922; but it is remembered as the origin of the naval aviat ...

. On July 18, 1918, he was promoted to lieutenant commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding ran ...

. In February 1919, he transferred from NAS Dinner Key to the Aviation Section in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, before reporting to Seaplane Division 1.

Interwar assignments (1919–1939)

Transatlantic crossing

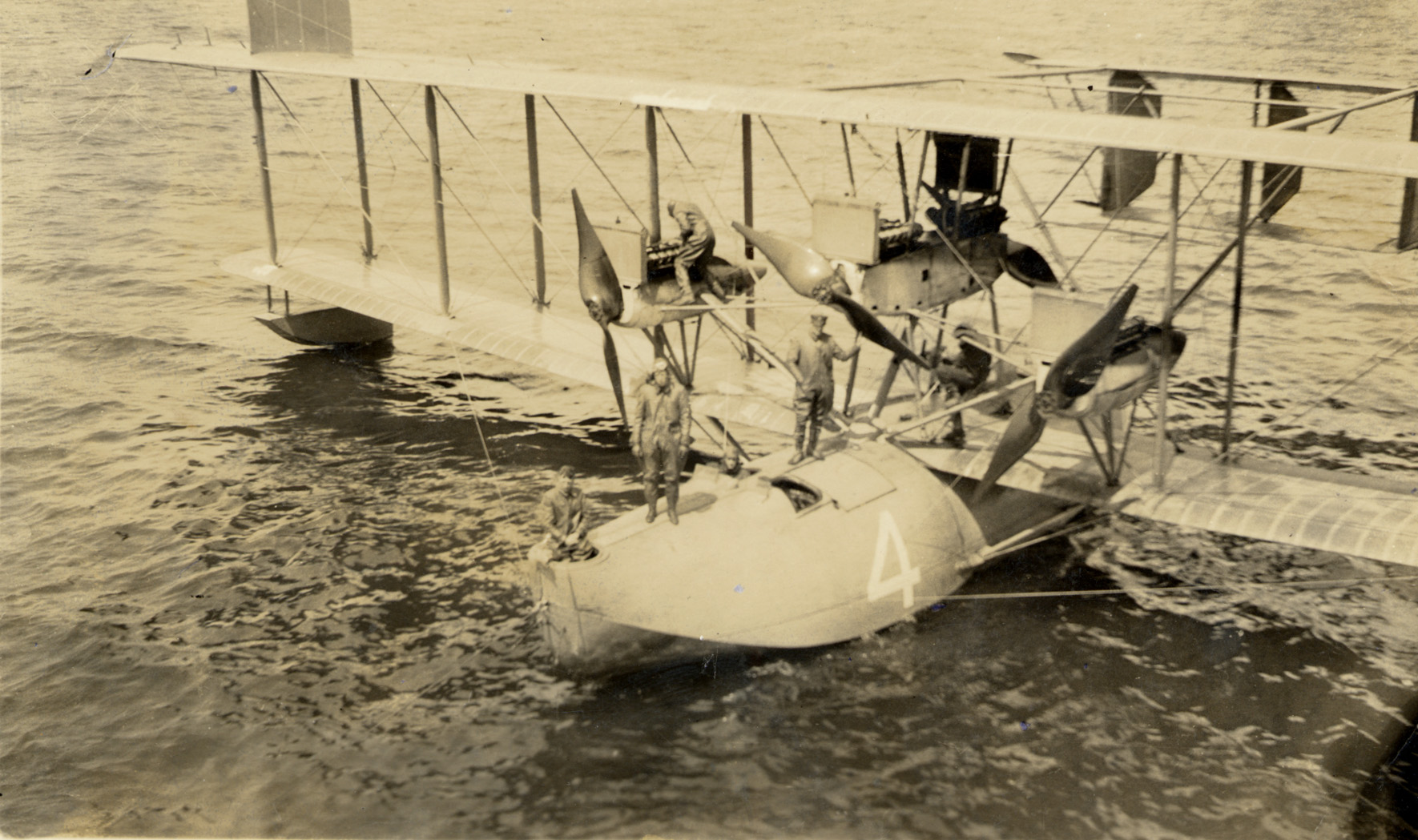

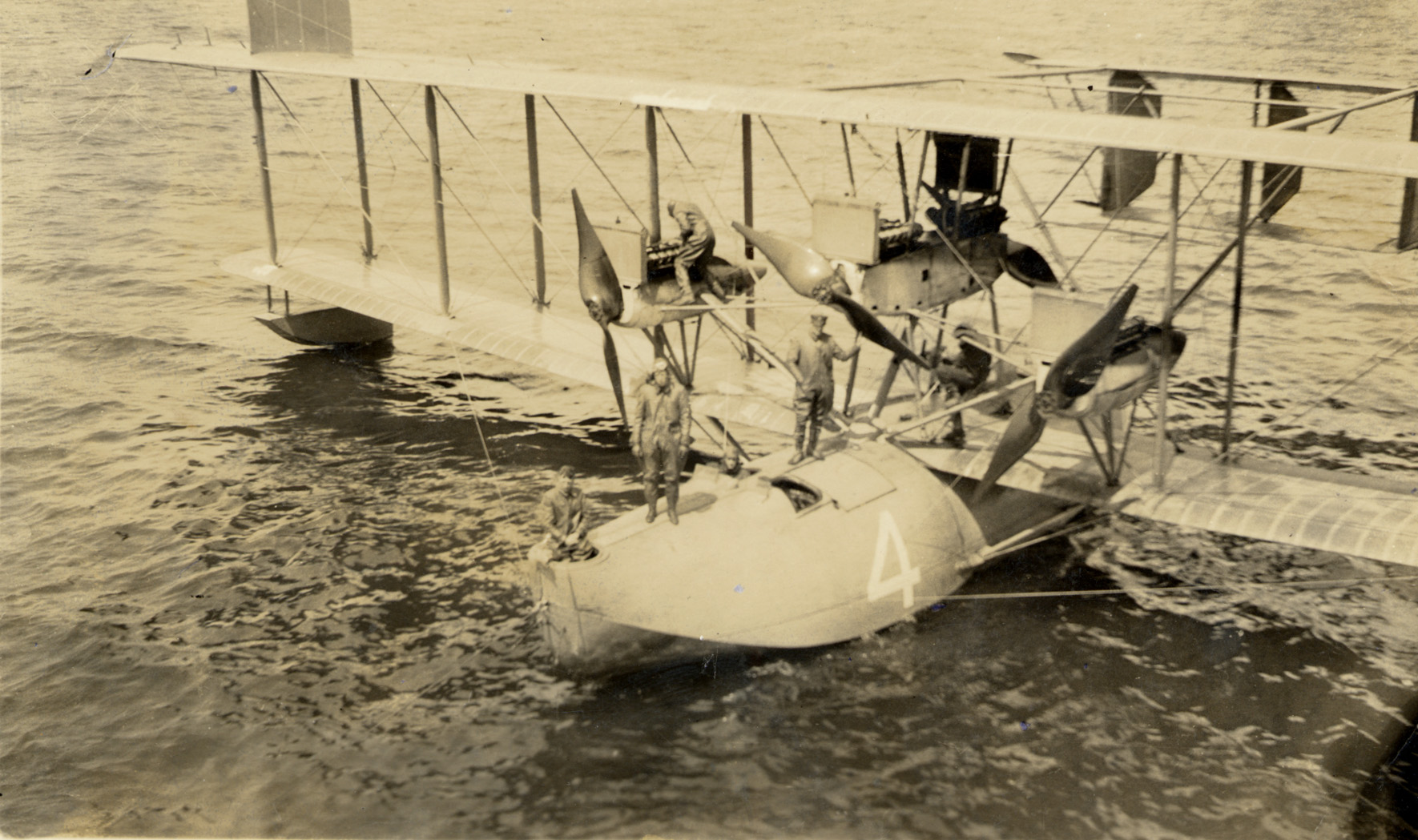

On May 10, 1919, Mitscher was among a group of naval aviators attempting the first

On May 10, 1919, Mitscher was among a group of naval aviators attempting the first transatlantic

Transatlantic, Trans-Atlantic or TransAtlantic may refer to:

Film

* Transatlantic Pictures, a film production company from 1948 to 1950

* Transatlantic Enterprises, an American production company in the late 1970s

* ''Transatlantic'' (1931 film) ...

crossing by air. Among the men involved were future admirals Jack Towers and Patrick N. L. Bellinger

Patrick Nieson Lynch Bellinger CBE (October 8, 1885 – May 30, 1962) was a highly decorated officer in the United States Navy with the rank of Vice Admiral. A Naval aviator and a naval aviation pioneer, he participated in the Trans-Atlantic fl ...

. Mitscher piloted NC-1 under the command of Bellinger, one of three Curtiss NC

The Curtiss NC (Curtiss Navy Curtiss, nicknamed "Nancy boat" or "Nancy") was a flying boat built by Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company and used by the United States Navy from 1918 through the early 1920s. Ten of these aircraft were built, the mos ...

flying boats that attempted the flight. Taking off from Newfoundland, he nearly reached the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

before heavy fog caused loss of the horizon, making flying in the early aircraft extremely dangerous. What appeared to be fairly calm seas at altitude turned out to be a heavy chop, and a control cable snapped while setting the aircraft down. Mitscher and his five crewmen were left to sit atop the upper wing of their "Nancy" while they waited to be rescued. Of the three aircraft making the attempt, only NC-4

The NC-4 was a Curtiss NC flying boat that was the first aircraft to fly across the Atlantic Ocean, albeit not non-stop. The NC designation was derived from the collaborative efforts of the Navy (N) and Curtiss (C). The NC series flying boats w ...

successfully completed the crossing. For his part in the effort Mitscher received the Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps' second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is eq ...

, the citation reading:

''"For distinguished service in the line of his profession as a member of the crew of the Seaplane NC-1, which made a long overseas flight from New Foundland to the vicinity of the Azores, in May 1919".''Mitscher was also made an officer of the

Order of the Tower and Sword

The Ancient and Most Noble Military Order of the Tower and of the Sword, of the Valour, Loyalty and Merit ( pt, Antiga e Muito Nobre Ordem Militar da Torre e Espada, do Valor, Lealdade e Mérito), before 1910 Royal Military Order of the Tower an ...

by the Portuguese government on June 3, 1919.

On October 14, 1919, Mitscher reported for duty aboard , a minelayer

A minelayer is any warship, submarine or military aircraft deploying explosive mines. Since World War I the term "minelayer" refers specifically to a naval ship used for deploying naval mines. "Mine planting" was the term for installing control ...

refitted as an "aircraft tender" that had been used as a support ship for the "Nancys'" transatlantic flight. He served under Captain Henry C. Mustin, another pioneering naval aviator. ''Aroostook'' was assigned temporary duties as flagship for the Air Detachment, Pacific Fleet. Mitscher was promoted to commander on July 1, 1921. In May 1922, he was detached from Air Squadrons, Pacific Fleet (San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United State ...

, California) to command Naval Air Station Anacostia

Anacostia is a historic neighborhood in Southeast Washington, D.C. Its downtown is located at the intersection of Good Hope Road and Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue. It is located east of the Anacostia River, after which the neighborhood is na ...

, D.C.

Service debates in Washington

After six months in command at Anacostia he was assigned to a newly formed department, the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics. Here as a young aviator he assisted Rear Admiral William Moffett in defending the Navy's interest in air assets. GeneralBilly Mitchell

William Lendrum Mitchell (December 29, 1879 – February 19, 1936) was a United States Army officer who is regarded as the father of the United States Air Force.

Mitchell served in France during World War I and, by the conflict's end, command ...

was advancing the idea that the nation was best defended by an independent service which would control all military aircraft. Though Mitscher was not a vocal member of the Navy's representatives, his knowledge of aircraft capabilities and limitations was instrumental in the Navy being able to answer Mitchell's challenge and retain their own airgroups. The debate culminated in the hearings before the Morrow Board, convened to study the best means of applying aviation to national defense. Mitscher testified before the board on October 6, 1925. General Mitchell sought public support for his position by taking his case directly to the people through the national press. For this action Mitchell was summoned for a court-martial. One of the witnesses called by the prosecution was Mitscher. In the end the Navy was left with its own air resources, and was allowed to continue to develop its own independent aviation branch.

Development of the carrier air arm

Over the next two decades Mitscher worked to develop naval aviation, taking assignments serving on theaircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s and , the seaplane tender , and taking command of Patrol Wing 1, in addition to a number of assignments ashore. ''Langley'' was the navy's first aircraft carrier. A converted collier, she could only make , thus limiting her ability to generate wind over her flight deck

The flight deck of an aircraft carrier is the surface from which its aircraft take off and land, essentially a miniature airfield at sea. On smaller naval ships which do not have aviation as a primary mission, the landing area for helicopte ...

and lift under the wings of her aircraft for launching and recovery. Aboard ''Langley'' Mitscher and other naval aviation pioneers developed many of the methods by which aircraft would be handled aboard U.S. Navy aircraft carriers. Many of these techniques continue to be used in the current-day U.S. Navy.

During this period Mitscher was assigned command of the air group for the newly commissioned aircraft carrier ''Saratoga''. Mitscher was the first person to land an airplane onto the flight deck of ''Saratoga'' as he brought his air group aboard. The vessel conducted mock attacks against the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

and Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the R ...

in a series of Fleet Problem The Fleet Problems are a series of naval exercises of the United States Navy conducted in the interwar period, and later resurrected by Pacific Fleet around 2014.

The first twenty-one Fleet Problems — labeled with roman numerals as Fleet Proble ...

exercises. The key lesson learned by the naval aviation officers during these exercises was the importance to locate and destroy the other side's flight decks as early as possible, while still preserving your own. In 1938, Mitscher was promoted to captain.

World War II

Between June 1939 and July 1941, Mitscher served as assistant chief of the

Between June 1939 and July 1941, Mitscher served as assistant chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics

The Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) was the U.S. Navy's material-support organization for naval aviation from 1921 to 1959. The bureau had "cognizance" (''i.e.'', responsibility) for the design, procurement, and support of naval aircraft and relate ...

.

Carrier commander

Mitscher's next assignment was as captain of the , being fitted out at Newport News Shipbuilding in Newport News, Virginia. Upon her commissioning in October 1941, he assumed command, taking ''Hornet'' to theNaval Station Norfolk

Naval Station Norfolk is a United States Navy base in Norfolk, Virginia, that is the headquarters and home port of the U.S. Navy's Fleet Forces Command. The installation occupies about of waterfront space and of pier and wharf space of the Hampt ...

for her training out period. She was there in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Newest of the Navy's fleet carriers, Mitscher worked hard to get ship and crew ready for combat. Following her shake-down cruise in the Caribbean, Mitscher was consulted on the possibility of launching long-range bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped from an air ...

s off the deck of a carrier. After affirming it could be done, the sixteen B-25 bombers of the Doolittle Raid

The Doolittle Raid, also known as the Tokyo Raid, was an air raid on 18 April 1942 by the United States on the Japanese capital Tokyo and other places on Honshu during World War II. It was the first American air operation to strike the Japa ...

were loaded on deck aboard ''Hornet'' for a transpacific voyage while ''Hornet''s own flight group was stored below deck in her hangar. ''Hornet'' rendezvoused with and Task Force 16

Task Force 16 (TF16) was one of the most storied task forces in the United States Navy, a major participant in a number of the most important battles of the Pacific War.

It was formed in mid-February 1942 around ''Enterprise'' (CV-6), with Vic ...

in the mid-Pacific just north of Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only state ...

. Under the command of Admiral Halsey, the task force proceeded in radio silence to a launch point from Japan. ''Enterprise'' provided the air cover for both aircraft carriers while ''Hornet''s flight deck was taken up ferrying the B-25s. ''Hornet'', then, was the real life "Shangri-la" that President Roosevelt

Roosevelt may refer to:

*Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919), 26th U.S. president

* Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945), 32nd U.S. president

Businesses and organisations

* Roosevelt Hotel (disambiguation)

* Roosevelt & Son, a merchant bank

* Rooseve ...

referred to as the source of the B-25s in his announcement of the bombing attack on Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and List of cities in Japan, largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, ...

.

Battle of Midway

During the

During the Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy under ...

, 4–7 June 1942, ''Hornet'' and ''Enterprise'' carried the air groups that made up the strike force of Task Force 16, while carried the aircraft of Task Force 17

Task Force 17 (TF17) was an aircraft carrier task force of the United States Navy during the Pacific Campaign of World War II. TF17 participated in several major carrier battles in the first year of the war.

TF17 was initially centered around ...

. Mitscher had command of the newest carrier in the battle and had the least experienced air group. As the battle unfolded, the Japanese carrier force was sighted early on June 4 at 234 degrees and about from Task Force 16, sailing on a northwest heading. In plotting their attack there was strong disagreement among the air group commanders aboard ''Hornet'' as to the best intercept course. Lieutenant Commander Stanhope C. Ring, in overall command of ''Hornet''s air groups, chose a course of 263 degrees, nearly true west, as the most likely solution to bring them to the Japanese carrier group. He had not anticipated the Japanese turning east into the wind while they recovered their aircraft. Lieutenant Commander John C. Waldron, in command of the torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

s of Torpedo Eight, strongly disagreed with Ring's flight plan. An aggressive aviator, he assured Mitscher he would get his group into combat and deliver their ordnance, no matter the cost.

Thirty minutes after the ''Hornet'' airgroups set out, Waldron broke away from the higher flying fighters

Fighter(s) or The Fighter(s) may refer to:

Combat and warfare

* Combatant, an individual legally entitled to engage in hostilities during an international armed conflict

* Fighter aircraft, a warplane designed to destroy or damage enemy warplan ...

and dive bombers, coming to a course of 240 degrees. This proved to be an excellent heading, as his Torpedo Eight squadron flew directly to the enemy carrier group's location "as though on a plumb line". They did so with no supporting fighters. On their way Waldron's Torpedo Eight happened to get picked up by ''Enterprise''s VF-6 fighter squadron flying several thousand feet above them. This group had launched last off ''Enterprise'' and had not been able to catch up with or locate the ''Enterprise'' dive bombers, but when Waldron dropped his group down to the deck to prepare for their attack the ''Enterprise'' fighters lost sight of them. Torpedo Eight was on its own.

The first of the carrier squadrons to locate the Japanese carriers, Waldron bore down upon the enemy. He brought his group in low, slowing for their torpedo drops. With no fighter escort and no other attackers on hand to split the defenders, his group was devastated by defending Japanese Zeros flying combat air patrol (CAP). All fifteen

The first of the carrier squadrons to locate the Japanese carriers, Waldron bore down upon the enemy. He brought his group in low, slowing for their torpedo drops. With no fighter escort and no other attackers on hand to split the defenders, his group was devastated by defending Japanese Zeros flying combat air patrol (CAP). All fifteen TBD Devastator

The Douglas TBD Devastator was an American torpedo bomber of the United States Navy. Ordered in 1934, it first flew in 1935 and entered service in 1937. At that point, it was the most advanced aircraft flying for the Navy and possibly for any na ...

s of VT-8 were shot down. Though not known at the time, the efforts of Torpedo Eight failed to deliver a hit on the Japanese carriers. Of the Torpedo Eight aircrews, only Ensign George H. Gay, Jr. survived. About twenty minutes later ''Enterprise''s Torpedo Six made their own attack, and was met with a similar hot reception. Again, no torpedo hits were made, but five of the aircraft managed to survive the engagement. Though failing to inflict any damage, the torpedo attacks did pull the Japanese CAP down and northeast of the carrier force, leaving the approach from other angles unhindered.

SBD

SBD may refer to:

* Douglas SBD Dauntless, a World War II American naval scout plane and dive bomber

* San Bernardino International Airport, airport identifier code SBD

* Savings Bank of Danbury, a bank headquartered in Connecticut

* Schottky bar ...

dive bombers from ''Enterprise'' arriving from the south flew over the Japanese carrier force to reach their tipping points almost unopposed. They delivered a devastating blow to and managed to put a bomb into as well, while SBDs coming from the east from ''Yorktown'' dove down upon and shattered her flight deck. All three ships were set ablaze, knocked out of the battle to sink later that day. While these attacks were in progress, Ring continued his search on a course of 260 degrees, flying to the north of the battle. Unable to find the enemy and running low on fuel, ''Hornet''s strike groups eventually turned back, either toward ''Hornet'' or to Midway Island

Midway Atoll (colloquial: Midway Islands; haw, Kauihelani, translation=the backbone of heaven; haw, Pihemanu, translation=the loud din of birds, label=none) is a atoll in the North Pacific Ocean. Midway Atoll is an insular area of the Unit ...

itself. All ten fighters in the formation ran out of fuel and had to ditch at sea. Several of her SBDs heading to Midway also ran out of fuel and had to ditch on their approach to the Midway base. Other SBDs attempting to return to ''Hornet'' were unable to locate her, and disappeared into the vast Pacific. All these aircraft were lost, though a number of the pilots were later rescued. Of ''Hornet''s air groups, only Torpedo Eight ended up reaching the enemy that morning. ''Hornet''s air groups suffered a 50 percent loss rate without achieving any combat results.

The battle was a great victory and Mitscher congratulated his crew for their efforts, but ''Hornet''s performance had not lived up to his expectations and he felt he had failed to deliver the results he should have done. In addition, he felt great regret for the loss of John Waldron and Torpedo Eight. For the next three years he would try to secure the award of the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valo ...

to the entire unit, but without success. The pilots of Torpedo Eight were eventually awarded the Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps' second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is eq ...

.

Mitscher's decisions in the battle have come under scrutiny largely due to the questionable actions of his subordinates and discrepancies in his After Action report. According to author Robert J. Mrazek, Mitscher backed up Ring's decision to take the heading of 263 degrees, as well as the decision to keep the fighters at high altitude, too high to effectively cover the torpedo bombers. Mrazek states that Waldron vehemently protested both decisions in front of Ring and Mitscher, but was overruled by the latter. At the time, American intelligence reports indicated that the Japanese might be operating their carriers in two groups, and the search plane contact report stated that only two carriers had been found. Mitscher and Ring had agreed on the westerly heading in order to search behind the enemy task force for a possible trailing group. A further controversy exists in that the only official report from ''Hornet'' states that the strike took a course heading of 239 degrees and missed the Japanese task force because it had turned north. This statement does not agree with some testimonies of Air Group Eight pilots and other evidence, most noticeably that none of the downed VF 10 pilots who were later rescued were found along the 238 course heading. Finally, the fact that no After Action reports were filed other than the one signed by Mitscher containing the 239 course heading is unusual. Mrazek believes that the lack of reports indicates a cover-up, possibly in an effort to protect Mitscher's reputation.

Commander Air Solomon Islands

Prior to the Midway operation Mitscher had been promoted to Rear Admiral in preparation for his next assignment, the command of Patrol Wing 2. Though Mitscher preferred to be at sea, he held this command until December when he was sent to the South Pacific as Commander Fleet Air,Nouméa

Nouméa () is the capital and largest city of the French special collectivity of New Caledonia and is also the largest francophone city in Oceania. It is situated on a peninsula in the south of New Caledonia's main island, Grande Terre, and ...

. Four months later in April 1943, Halsey moved Mitscher up to Guadalcanal, assigning him to the thick of the fight as Commander Air, Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capit ...

(COMAIRSOLS). Here Mitscher directed an assortment of Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

, Navy, Marine and New Zealand aircraft in the air war over Guadalcanal and up the Solomon chain. Said Halsey: "I knew we'd probably catch hell from the Japs in the air. That's why I sent Pete Mitscher up there. Pete was a fighting fool and I knew it." Short on aircraft, fuel and ammunition, the atmosphere on Guadalcanal was one of dogged defense. Mitscher brought a fresh outlook, and instilled an offensive mindset to his assorted air commands. Mitscher later said this assignment managing the constant air combat over Guadalcanal was his toughest duty of the war.

Battles for the Central Pacific

Returning to the Central Pacific as Commander, Carrier Division 3, Mitscher was given primary responsibility for the development and operations of a newly formed

Returning to the Central Pacific as Commander, Carrier Division 3, Mitscher was given primary responsibility for the development and operations of a newly formed Fast Carrier Task Force

The Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 38 when assigned to Third Fleet, TF 58 when assigned to Fifth Fleet), was the main striking force of the United States Navy in the Pacific War from January 1944 through the end of the war in August 1945. The task ...

, at that time operating as Task Force 58 as part of Admiral Raymond Spruance

Raymond Ames Spruance (July 3, 1886 – December 13, 1969) was a United States Navy admiral during World War II. He commanded U.S. naval forces during one of the most significant naval battles that took place in the Pacific Theatre: the Battle ...

's Fifth Fleet. To that point in the conflict carriers had been able to bring enough airpower to bear to inflict significant damage on opposing naval forces, but they always acted as a raiding group against land bases. They would approach their objective, inflict damage, and then escape into the vast reaches of the Pacific. Even the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, devastating though it was, was a carrier raid. Naval airpower was not thought to have the capacity to challenge land-based airpower over any length of time. Mitscher was about to change that, leading U.S. naval airpower into a new realm of operations.

The fleet had recently completed operations in the Gilbert Islands, taking

The fleet had recently completed operations in the Gilbert Islands, taking Tarawa

Tarawa is an atoll and the capital of the Republic of Kiribati,Kiribati

''

During 1944 and 1945, Vice Admiral Mitscher's fast carriers, whether designated Task Force 38 or Task Force 58, spearheaded the thrust against the heart of the Japanese Empire, covering successively the invasion of the Palaus, the

During 1944 and 1945, Vice Admiral Mitscher's fast carriers, whether designated Task Force 38 or Task Force 58, spearheaded the thrust against the heart of the Japanese Empire, covering successively the invasion of the Palaus, the

Mitscher was considered to be a very quiet man. He rarely spoke, never engaged in small talk and would never discuss mission details at the mess table. On the rare occasions when he would enter into conversation it would be about fishing, the love of which he picked up in his middle years. Mitscher relaxed by reading cheap murder mysteries, and when at sea he would always have one with him. Though he appeared distant and severe to those who did not know him, in truth he held a deep affection for his men and possessed a dry sense of humor. An example of his humor was displayed in his gentle ribbing of his chief-of-staff, Captain

Mitscher was considered to be a very quiet man. He rarely spoke, never engaged in small talk and would never discuss mission details at the mess table. On the rare occasions when he would enter into conversation it would be about fishing, the love of which he picked up in his middle years. Mitscher relaxed by reading cheap murder mysteries, and when at sea he would always have one with him. Though he appeared distant and severe to those who did not know him, in truth he held a deep affection for his men and possessed a dry sense of humor. An example of his humor was displayed in his gentle ribbing of his chief-of-staff, Captain

Admiral Marc Mitscher, U.S. Navy Biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mitscher, Marc 1887 births 1947 deaths People from Hillsboro, Wisconsin American people of German descent People from Oklahoma City United States Naval Academy alumni Aviators from Wisconsin Military personnel from Wisconsin United States Naval Aviators Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States) Recipients of the Order of the Tower and Sword United States Navy admirals United States Navy World War II admirals Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal Recipients of the Legion of Merit Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Deaths from coronary thrombosis

''

Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Intern ...

. The idea that land-based air support was necessary to successfully conduct an amphibious operation was traditional doctrine. The Marshalls would be the first key step in the Navy's march across the Pacific to reach Japan. Mitscher's objective was to weaken Japanese air defenses in the Marshalls and limit their capability of flying in reinforcements, in preparation for a U.S. invasion of the Marshalls, code named Operation Flintlock. Intelligence estimates of the Japanese defenders of the Marshall Islands believed they had approximately 150 aircraft at their disposal. Two days before the intended landings Mitscher's task groups approached to within of the Marshalls and launched their air strikes, fighters first to soften up the defenders, followed by bombers to destroy ground emplacements, buildings, supplies, and the defenders' airfields. It was thought it would take two days to attain air superiority. Though the Japanese battled briskly, they lost control of the skies over the Marshall Islands by noon of the first day. What came next was an aerial bombardment of the Japanese defenses, followed by a naval bombardment

Naval gunfire support (NGFS) (also known as shore bombardment) is the use of naval artillery to provide fire support for amphibious assault and other troops operating within their range. NGFS is one of a number of disciplines encompassed by the ...

from the big guns of Spruance's surface force. The two days of destruction saved a great many lives of the Marines that were landed. The Japanese were estimated to have lost 155 aircraft. Mitscher's task force lost 57 aircraft, from which 31 pilots and 32 crewmen were lost. But the manner in which the fast carrier task force was employed established a pattern for future Pacific operations. In his summary report for the month of January, Admiral Nimitz commented it was "typical of what may be expected in the future."

Next, Mitscher led Task Force 58 in a raid against Truk, Satawan and Ponape (February 17–18). This was a big step up. The idea of purposely sailing into the range of a major Japanese naval and air base brought great unease to Mitscher's airmen. Said one: "They announced our destination over the loudspeaker once we were underway. It was Truk. I nearly jumped overboard." But Mitscher felt confident they could succeed. As tactical commander of the striking force, he developed techniques that would help give his airmen the edge of surprise. In Operation Hailstone

Operation Hailstone ( ja, トラック島空襲, Torakku-tō Kūshū, lit=airstrike on Truk Island), 17–18 February 1944, was a massive United States Navy air and surface attack on Truk Lagoon conducted as part of the American offensive drive ...

, Mitscher's forces approached Truk from behind a weather front to launch a daybreak raid that caught many of the defenders off guard. The airmen brought devastation to the heavily defended base, destroying 72 aircraft on the ground and another 56 in the air, while a great number of auxiliary vessels and three warships were sunk in the lagoon. Chuckling over the pre-raid fears, Mitscher commented, "All I knew about Truk was what I'd read in the '' National Geographic''."

Through the spring of 1944 Task Force 58 conducted a series of raids on Japanese air bases across the Western Pacific, first in the Mariana

Mariana may refer to:

Literature

* ''Mariana'' (Dickens novel), a 1940 novel by Monica Dickens

* ''Mariana'' (poem), a poem by Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson

* ''Mariana'' (Vaz novel), a 1997 novel by Katherine Vaz

Music

*"Mariana", a so ...

and Palau Islands

Palau,, officially the Republic of Palau and historically ''Belau'', ''Palaos'' or ''Pelew'', is an island country and microstate in the western Pacific. The nation has approximately 340 islands and connects the western chain of the Caro ...

, followed by a raid against Japanese bases in the Hollandia area. These attacks demonstrated that the air power of Task Force 58 was great enough to overwhelm the air defenses of not just a single island air base, or several bases on an island, but the air bases of several island groups at one time. The long-held naval rule that fleet operations could not be conducted in the face of land-based air power was brushed aside.

In the ensuing year Mitscher's aviators devastated Japanese carrier forces in the Battle of the Philippine Sea

The Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 19–20, 1944) was a major naval battle of World War II that eliminated the Imperial Japanese Navy's ability to conduct large-scale carrier actions. It took place during the United States' amphibious invas ...

—also known as the "Great Marianas Turkey Shoot"—during June 1944. Memorably, when a very long-range U.S. Navy follow-up strike had to return to their carriers in darkness, Mitscher ordered all the carriers' flight deck landing lights turned on, risking submarine attack to give his aviators the best chance of being recovered.

On 26 August 1944, when Admiral William Halsey relieved Admiral Raymond Spruance as the fleet commander, the ships of the Fifth Fleet became the Third Fleet, and the subordinate Fast Carrier Task Force 58 became Task Force 38. The redesignated task force remained commanded by Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher. One of the most unfortunate events of the Pacific war occurred on the morning of 21 September 1944, when spotter planes from one of TF 38's carriers came across the MATA-27 convoy and a full scale attack soon was launched. All eleven ships were sunk, including the ''Toyofuku Maru'', which received direct hits from two aerial torpedoes and three bombs, sinking within five minutes; unfortunately, the ''Toyofuku Maru'' was carrying Dutch and British prisoners of war below decks, of which 1,047 drowned. This was learned only after the war's end.

Facing the kamikaze threat

During 1944 and 1945, Vice Admiral Mitscher's fast carriers, whether designated Task Force 38 or Task Force 58, spearheaded the thrust against the heart of the Japanese Empire, covering successively the invasion of the Palaus, the

During 1944 and 1945, Vice Admiral Mitscher's fast carriers, whether designated Task Force 38 or Task Force 58, spearheaded the thrust against the heart of the Japanese Empire, covering successively the invasion of the Palaus, the liberation of the Philippines

Liberation or liberate may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Liberation'' (film series), a 1970–1971 series about the Great Patriotic War

* "Liberation" (''The Flash''), a TV episode

* "Liberation" (''K-9''), an episode

Gaming

* '' Liberati ...

, and the conquests of Iwo Jima and Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

. On 26 January 1945, the Third Fleet again became the Fifth Fleet. During the Okinawa operation there was a weather-caused delay in the Army preparing serviceable air bases. To provide essential air support to the intense ground operations, Mitscher was obliged to keep then-Task Force 58 sailing in a box on station some east of Okinawa, often in stormy weather and heavy seas, for the next two months. During this time they were subject to air attack around the clock, and the psychological pressures of warding off these attacks were enormous. Rarely did a night go by that all the ships' crews were not called to general quarters, and the days were worse. Mitscher won his second Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps' second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is eq ...

for the critical success of TF 38 over the period of October 22–30, 1944, both away from and also in direct support of the Battle of Leyte Gulf. He won his third Navy Cross for the critical success of TF 58 over the period of January 27 – May 27, 1945, both away from and also in direct support of the battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

On 11 May 1945 Mitscher's flagship was struck by kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending t ...

s, knocking her out of the operation and causing much loss of life. Half of Mitscher's staff officers were killed or wounded, and Mitscher was forced to shift his command to ''Enterprise''. ''Enterprise'' at that time was functioning as a "night carrier," launching and recovering her aircraft in the dark to protect the fleet against land-based Japanese bomber and torpedo aircraft slipping in to attack the fleet in the relative safety of night. When ''Enterprise'' too was struck by a kamikaze attack, Mitscher had to transfer once more, this time to , the carrier that earlier had been damaged by a long-range kamikaze attack at Ulithi

Ulithi ( yap, Wulthiy, , or ) is an atoll in the Caroline Islands of the western Pacific Ocean, about east of Yap.

Overview

Ulithi consists of 40 islets totaling , surrounding a lagoon about long and up to wide—at one of the larges ...

. Throughout this period Mitscher repeatedly led the fast carriers northward to attack air bases on the Japanese home islands

The Japanese archipelago (Japanese: 日本列島, ''Nihon rettō'') is a group of 6,852 islands that form the country of Japan, as well as the Russian island of Sakhalin. It extends over from the Sea of Okhotsk in the northeast to the East Chin ...

. On 27 May 1945, Halsey for the last time relieved Spruance as fleet commander; the next day Vice Admiral John S. McCain relieved Vice Admiral Mitscher as Commander, Task Force 38. Commenting on Admiral Mitscher upon his return from the Okinawa campaign, Admiral Nimitz said, "He is the most experienced and most able officer in the handling of fast carrier task forces who has yet been developed. It is doubtful if any officer has made more important contributions than he toward extinction of the enemy fleet." Exhausted and ill after a heart attack, Mitscher went to Washington, DC, to serve as Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Air.

Post-war

At the conclusion of World War II, and in the face of markedly reduced U.S. military spending, a political battle ensued in America over the need for, and the nature of, a post-war military, with advocates from the Army Air Forces insisting that with the development of the atomic bomb the nation could be defended by the devastating power that strategic bombers could deliver, thereby doing away with the need for Army or Navy forces. In their view, air assets in the Navy should be brought under the control of the soon-to-be-formedAir Force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an ...

. In the face of such proposals Mitscher remained a staunch advocate for naval aviation, and went so far as to release the following statement to the press:

Japan is beaten, and carrier supremacy defeated her. Carrier supremacy destroyed her army and navy air forces. Carrier supremacy destroyed her fleet. Carrier supremacy gave us bases adjacent to her home islands, and carrier supremacy finally left her exposed to the most devastating sky attack – the atomic fission bomb – that man has suffered.

When I say carrier supremacy defeated Japan, I do not mean air power in itself won the Battle of the Pacific. We exercised our carrier supremacy as part of a balanced, integrated air-surface-ground team, in which all hands may be proud of the roles assigned them and the way in which their duties were discharged. This could not have been done by a separate air force, exclusively based ashore, or by one not under Navy control.By July 1946, when he was serving as Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (Air), Mitscher received, among other awards, two Gold Stars signifying his second and third

Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps' second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is eq ...

and the Distinguished Service Medal Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) is a high award of a nation.

Examples include:

*Distinguished Service Medal (Australia) (established 1991), awarded to personnel of the Australian Defence Force for distinguished leadership in action

* Distinguishe ...

with two Gold Stars.

He served briefly as commander 8th Fleet and on 26 September 1946 became Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, with the rank of admiral.

While in that assignment, Mitscher died on 3 February 1947 at the age of 60 of a coronary thrombosis

Coronary thrombosis is defined as the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel of the heart. This blood clot may then restrict blood flow within the heart, leading to heart tissue damage, or a myocardial infarction, also known as a heart at ...

at Norfolk, Virginia. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

.

Mitscher's style as military commander

Though reserved and quiet, Mitscher possessed a natural authority. He could check a man with a single question. He was intolerant of incompetence and would relieve officers who were not making the grade, but was lenient with what he would consider honest mistakes. Harsh discipline, he believed, ruined more men than it made. He was not forgetful of the abuse he took at the Naval Academy. He believed pilots could not be successfully handled with rigid discipline, as what made for a good pilot was an independence that inflexible discipline destroyed. At the same time he was insistent on rigid "air discipline" and he would break a man who violated it.Naval aviation tactics

Before most other officers in the high command of the U.S. Navy, Mitscher had a grasp of the potential sudden, destructive power that air groups represented. The change in the operation of carriers from single or paired carriers with support vessels to task groups of three or four carriers was a Mitscher concept, which he implemented for the purpose of concentrating the fighter aircraft available for a better air defense of the carriers. Offensively, Mitscher trained his air groups to engage in air attacks which delivered a maximum destructive force upon the enemy with the least amount of loss to his aviators. He sought well coordinated attacks. In a typical Mitscher-style air attack, fighter aircraft would come at the targets first, strafing the enemy ships to suppress their defensive anti-aircraft fire. In plain terms he intended his fighter pilots to wound or kill the target ship's anti-aircraft gun crews. Following the fighter runs, the ordnance-carrying aircraft would execute bombing and torpedo runs, preferably simultaneously to overburden the ship's defenses and negate evasive maneuvers. The attack would be completed in a few minutes. Once the attack was delivered the air groups would leave, as suddenly as they had arrived.Leadership

Mitscher's command style was one of few words. His small frame belied the authority he carried. A raised eyebrow was all he needed to indicate he was not pleased with the effort of one of his officers. He was not patient with incompetent personnel, yet he was forgiving of what he considered "honest" mistakes, and would allow airmen a second chance when other officers would have washed them out. He placed tremendous value on his pilots and had great respect for the risks they were willing to accept in attacking the enemy. His practice was for the flight leaders of the air groups of the carrier he was commanding from to come up to the flag bridge and report following the completion of their missions. He valued greatly the information he received from the men who had been in the air on the scene. He was devoted to these men, and made a great effort to recover as many downed aircrew as possible. One place this was demonstrated was at theBattle of the Philippine Sea

The Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 19–20, 1944) was a major naval battle of World War II that eliminated the Imperial Japanese Navy's ability to conduct large-scale carrier actions. It took place during the United States' amphibious invas ...

, where he ordered the fleet flight decks illuminated so pilots returning in the dark and very low on fuel (many aircraft had to ditch into the sea) would have a better chance of finding the carriers, despite the risk from enemy submarines. He hated to lose a man, either adrift at sea, or worse, captured by the Japanese. Having spent time adrift on a downed aircraft himself, he was always deeply distressed that the numbers of rescued airmen were not higher.

Personality

Mitscher was considered to be a very quiet man. He rarely spoke, never engaged in small talk and would never discuss mission details at the mess table. On the rare occasions when he would enter into conversation it would be about fishing, the love of which he picked up in his middle years. Mitscher relaxed by reading cheap murder mysteries, and when at sea he would always have one with him. Though he appeared distant and severe to those who did not know him, in truth he held a deep affection for his men and possessed a dry sense of humor. An example of his humor was displayed in his gentle ribbing of his chief-of-staff, Captain

Mitscher was considered to be a very quiet man. He rarely spoke, never engaged in small talk and would never discuss mission details at the mess table. On the rare occasions when he would enter into conversation it would be about fishing, the love of which he picked up in his middle years. Mitscher relaxed by reading cheap murder mysteries, and when at sea he would always have one with him. Though he appeared distant and severe to those who did not know him, in truth he held a deep affection for his men and possessed a dry sense of humor. An example of his humor was displayed in his gentle ribbing of his chief-of-staff, Captain Arleigh Burke

Arleigh Albert Burke (October 19, 1901 – January 1, 1996) was an admiral of the United States Navy who distinguished himself during World War II and the Korean War, and who served as Chief of Naval Operations during the Eisenhower and Kenn ...

. Burke had come to Mitscher from destroyers, and it was well known that he preferred a fighting command over his new role as chief-of-staff. When a destroyer came alongside to refuel from their flagship, a carrier, the admiral directed a Marine sentry nearby: "Secure Captain Burke, till that destroyer casts off."

Relations toward superior officers

Mitscher had tactical control of Task Force 58/38 and directed its subordinate task groups. Strategic control was held by Spruance or Halsey. While Spruance granted his subordinates great authority, Halsey exercised much tighter control, such that Commander, Third Fleet, was for all practical purposes Commander, Task Force 38 as well; this was clearly and repeatedly seen in the battle of Leyte Gulf. But however much he may have disagreed with an order, once a decision was made by either of his superiors Mitscher would implement the decision without complaint. This was most prominently exemplified in the last two major naval battles of the war: theBattle of the Philippine Sea

The Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 19–20, 1944) was a major naval battle of World War II that eliminated the Imperial Japanese Navy's ability to conduct large-scale carrier actions. It took place during the United States' amphibious invas ...

and the Battle of Leyte Gulf. In each case Mitscher recommended a course of action which sharply differed from that subsequently ordered by his fleet commander; he executed those orders without further debate or protest.

Nevertheless, late in the war, Mitscher did preempt U.S. Fifth Fleet commander Admiral Raymond Spruance in stopping a Japanese naval sortie, centered around the super-battleship ''Yamato,'' from reaching Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

. Upon receiving contact reports from submarines ''Threadfin'' and ''Hackleback'' early on 7 April 1945, Spruance ordered Task Force 54, which consisted of older Standard-type battleships under the command of Rear Admiral Morton Deyo

Vice Admiral Morton Lyndholm Deyo (1 July 1887 – 10 November 1973) was an officer in the United States Navy, who was a naval gunfire support task force commander of World War II.

Born on 1 July 1887 in Poughkeepsie, New York, he graduated from ...

(and which were then engaged in shore bombardment of Okinawa), to prepare to intercept and destroy the Japanese sortie. Deyo began to plan how to execute his orders. Mitscher, however, preempted using the American battleship force by launching on his own initiative a massive air strike from his three carrier task groups then in range of the Japanese surface formation—without informing Spruance until after the launches were completed. As a senior naval aviation officer, "Mitscher had spent a career fighting the battleship admirals who had steered the navy's thinking for most of hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

century. One of those was his immediate superior, Raymond Spruance. Mitscher ay havefelt a stirring of battleship versus aircraft carrier rivalry. Though the carriers had mostly fought the great battles of the Pacific, whether air power alone could prevail over a surface force had not been proven beyond all doubt. Here was an opportunity to end the debate forever." After being informed of Mitscher's launches, Spruance agreed that the air strikes could go ahead as planned. As a contingency should the air strikes not be successful, Spruance planned to assemble a force of six new fast battleships (, , , , , and ), together with seven cruisers (including the newly-arrived large cruisers and ), escorted by 21 destroyers, and to prepare for a surface engagement with ''Yamato.'' Mitscher's air strikes sank ''Yamato'', light cruiser ''Yahagi'', and four destroyers (the other four fled back to Japanese ports), at the cost of ten aircraft and twelve aircrew lost.

Legacy

Two ships of the Navy have been named USS ''Mitscher'' in his honor: the post-World War II frigate, , later re-designated as the guided-missile destroyer (DDG-35), and the currently serving guided-missile destroyer, . The airfield and a street at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar (formerly Naval Air Station Miramar) were also named in his honor (Mitscher Field and Mitscher Way). Mitscher Hall at the United States Naval Academy houses chaplain offices, meeting rooms, and an auditorium. In 1989, Mitscher was inducted into theInternational Air & Space Hall of Fame

The International Air & Space Hall of Fame is an honor roll of people, groups, organizations, or things that have contributed significantly to the advancement of aerospace flight and technology, sponsored by the San Diego Air & Space Museum. Si ...

at the San Diego Air & Space Museum

San Diego Air & Space Museum (SDASM, formerly the San Diego Aerospace Museum) is an aviation and space exploration museum in San Diego, California, United States. The museum is located in Balboa Park and is housed in the former Ford Building, ...

.Sprekelmeyer, Linda, editor. ''These We Honor: The International Aerospace Hall of Fame''. Donning Co. Publishers, 2006. .

The words of Admiral Arleigh Burke

Arleigh Albert Burke (October 19, 1901 – January 1, 1996) was an admiral of the United States Navy who distinguished himself during World War II and the Korean War, and who served as Chief of Naval Operations during the Eisenhower and Kenn ...

, his wartime chief-of-staff, provide the greatest tribute and recognition of his leadership:

: "He spoke in a low voice and used few words. Yet, so great was his concern for his people — for their training and welfare in peacetime and their rescue in combat — that he was able to obtain their final ounce of effort and loyalty, without which he could not have become the preeminent carrier force commander in the world. A bulldog of a fighter, a strategist blessed with an uncanny ability to foresee his enemy's next move, and a lifelong searcher after truth and trout streams, he was above all else — perhaps above all other — a Naval Aviator."

The character Pete Richards, played by Walter Brennan

Walter Andrew Brennan (July 25, 1894 – September 21, 1974) was an American actor and singer. He won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his performances in '' Come and Get It'' (1936), ''Kentucky'' (1938), and '' The Westerner ...

in Task Force (film)

''Task Force'' is a 1949 war film filmed in black-and-white with some Technicolor sequences about the development of U.S. aircraft carriers from to . Although Robert Montgomery was originally considered for the leading role, the film stars G ...

is loosely based on Mitscher.

Awards and decorations

Ribbon bar of Admiral Mitscher:See also

*List of military figures by nickname

This is a list of military figures by nickname.

0-9

*"31-Knot Burke" – Arleigh Burke, U.S. Navy destroyer commander (for being unable to meet his habitual maximum speed during one operation due to limited recent maintenance)

A

*"ABC" – An ...

References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * Uses recently translated Japanese sources. * * Taylor, Theodore. ''The Magnificent Mitscher''. New York: Norton, 1954; reprinted Annapolis, Md.:Naval Institute Press

The United States Naval Institute (USNI) is a private non-profit military association that offers independent, nonpartisan forums for debate of national security issues. In addition to publishing magazines and books, the Naval Institute holds se ...

, 1991. .

* Willmott, H.P. (1984) "June, 1944" Blandford Press

External links

Admiral Marc Mitscher, U.S. Navy Biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mitscher, Marc 1887 births 1947 deaths People from Hillsboro, Wisconsin American people of German descent People from Oklahoma City United States Naval Academy alumni Aviators from Wisconsin Military personnel from Wisconsin United States Naval Aviators Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States) Recipients of the Order of the Tower and Sword United States Navy admirals United States Navy World War II admirals Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal Recipients of the Legion of Merit Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Deaths from coronary thrombosis